By Joanna Cohan Scherer

Analysis of the Photographs

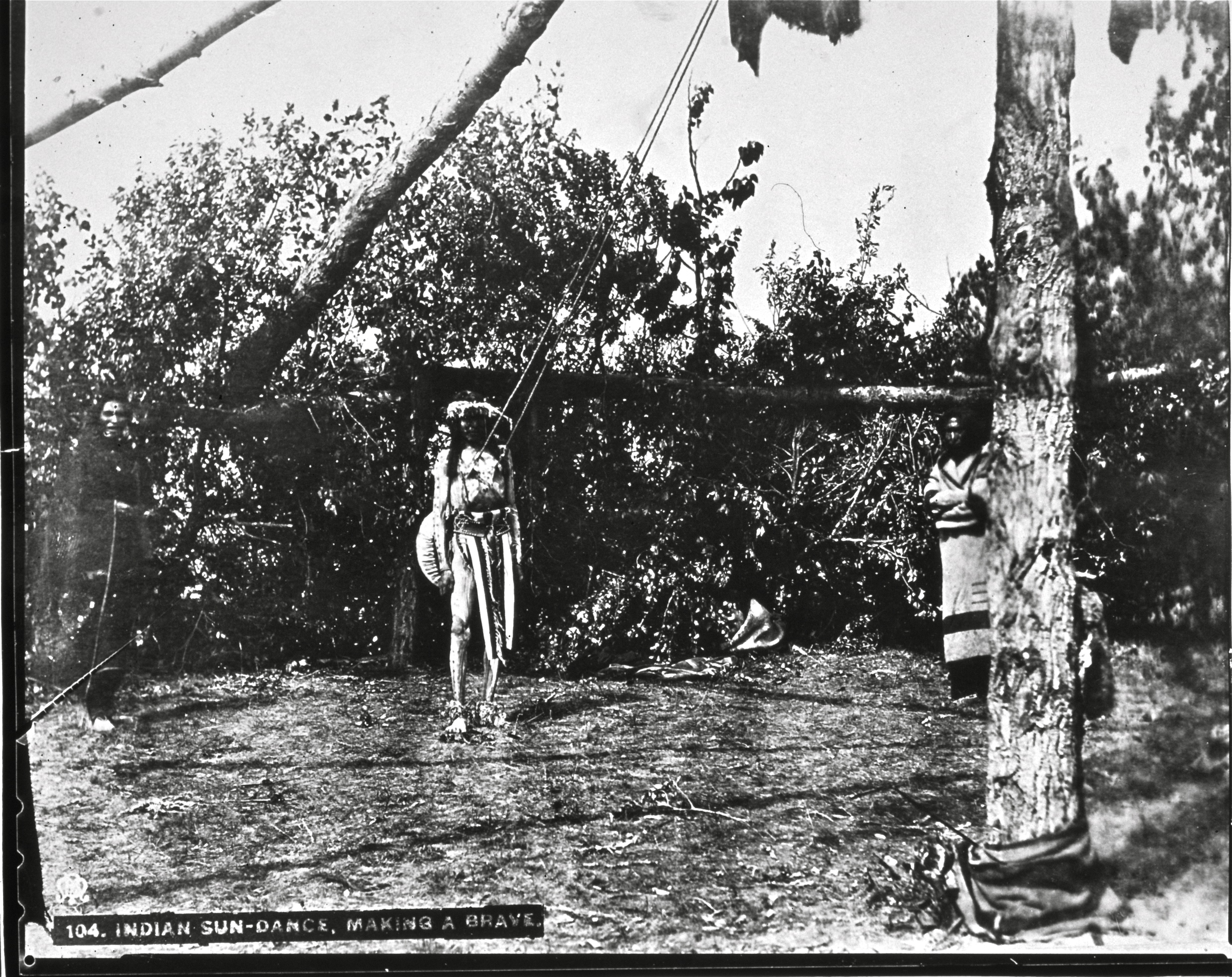

Eight different Boorne images exist as 8x10 and 5x8 original glass plate negatives, made with a slow wet-plate camera, that had to be developed soon after exposure. Of the eight images five are of the self-sacrifice and three of the preparations for the Medicine Lodge ceremony. According to the photographer (Boorne 1936:11), of all the plates he exposed that July evening in 1887, "only two were found to be worth anything, […] one really good one, when Wolf-Shoe earned his bonus."

Figs. 3 (right) and 5 are no doubt the two he felt "worth anything." This deduction is based on the number of copy negatives and cropped (detail) negatives that exist of these two images. The image labeled "104" (Fig. 5) has six copy negatives (the original no longer appears to exist). Several of these are cropped to focus on the participant pulling himself free of the rope. The print labeled "105" (Fig. 3, right) has four copy negatives (the original negative is cracked); views labeled "B1010" and "B1006" are details focusing again on the participant undergoing the self-sacrifice and eliminating the spectators. The cropping of these two images is a clear indication that the photographer was interested in having his viewer focus on the self-sacrifice of the two different individuals.

The series was later purchased by Charles W. Mathers who bought out Boorne and Ernest Gundry May’s Edmonton studio in 1892. Later some of the images were copyrighted by Ernest Brown who purchased Mathers studio in 1904. Thus the names appearing on the bottom of many of these prints reflect not the original photographer of the image, but the history of the studios which subsequently purchased them.11 The 900 series numbers appearing on the face of prints B-990, 991, 998, 981, 984, and 985 are likely Brown's numbering system. Boorne’s numbers are probably the 104 and 105, appearing on the face of the photographs.

According to the photographer's own notes, "this photograph [Fig. 5] was published in many Canadian and also American magazines and newspapers at the time, and I was awarded a gold medal at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893, where I exhibited it with other Indian photographs, by request, in the C.P.R. [Canadian Pacific Railroad] Section.12 I was also awarded other Canadian medals for it" (Boorne 1936:4). It was promoted in the Boorne and May souvenir album of 1890 (Fig 6), and an engraving based on Fig. 3 (center) is reproduced in Aberdeen (1893). The self-sacrifice photograph used by itself again and again gave the impression that this was the most significant activity of the Medicine Lodge ceremony. Thus the icon was in place by 1890 that perpetuated the stereotype of the Indian as a barbaric, uncivilized, naked savage.

Although in later years Boorne claimed these were the only photos of the self-sacrifice ritual as practiced by the Blood Indians, we know the ceremony was photographed on at least one other occasion in 1892 by Robert N. Wilson, the Blood Indian agent (Dempsey 1980:48). Copies of the Wilson photo are in the Glenbow Archives, the American Museum of Natural History (reproduced in Scherer 1973:128-129) and the Peabody Museum at Yale (Fig. 7). Boorne had a vested interest in maintaining his photographic exclusive domain, for it is clear that his purpose from the beginning was commercial, not scientific.

Looking at the eight 1887 Boorne Sun Dance photographs as a group we can observe certain facts. First, the lodge itself was made in a traditional manner (see Fig. 2) using brush and branches of trees. By 1895, among the Plains Cree in Saskatchewan, for example, canvas was replacing branches in covering for the lodge. Second, we can see that at least three different individuals participated in the piercing self-sacrifice ritual (Fig. 3, right), verifying information presented by the photographer in his written accounts.

Next Section: Non-Indian Presence at the Ceremony

11 Additional information on the Ernest Brown studio can be found in Scherer (1981:9-10).

12 The 1893 World Columbian International Exposition (the Chicago World’s Fair), was held to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus' landing in America. Included were many anthropological exhibits of indigenous peoples in living museum settings complete with Native houses and demonstrating their crafts and ceremonies. Franz Boas (then a young immigrant scientist), George Hunt (Kwakuitl consultant), Frederick Ward Putnam (Director, Peabody Museum at Harvard) and others oversaw many displays. Northwest Coast Indians were a focus, but Navajos, Apaches, Penobscots, Iroquois, Arawaks, and others were also present. In addition there were "280 Egyptians and Sudanese in a Cairo street, 147 Indonesians in a Javanese village, 58 Eskimos from Labrador, a party of bare-breasted Dahomans in a West African setting, Malays, Samoans, Fijians, Japanese, Chinese, as well as an Irish village with both Donegal and Blarney castles and a reconstructed old Vienna Street" (Cole 1985: 128).

Along with this spectacle and the showing of Boorne’s Medicine Lodge self-sacrifice photo of the Blood Indians there was an incident in which George Hunt helped put on a "Sun Dance." The New York Times, August 19, 1893, and The Sunday Times (London), August 20, 1893, labeled it "A Brutal Exhibition" and "Horrible Scene at the Fair," respectively. The incident was investigated and confirmed "although 'the barbarism I think was not as great as described,' some of the cruel and revolting scenes as reported in The Sunday Times had occurred. So much repugnance had been created that exposition authorities promised to halt any repeat performance" (Cole 1985: 130). Thus, self-sacrifice as the epitome of Native American barbarism was well in place.